Note from the Author: I wrote this piece in March 2022. I did not get around to publishing it anywhere. Hence, posting it here. Some of the information mentioned here is outdated.

Introduction

India has pursued a space program since the 1960s with the intention of benefitting its people for the past sixty years. For this period, the program was dominated by a single government player with an innovative production capability nurtured through these years. But, the Indian government now wants private players to play a bigger role – to design products, develop them, and market them to the world. Against this backdrop, the Indian Government opened up the space sector in 2020. This led to the need to make policies and institutions that would help India tap into this hidden potential.

Opening up India’s Space Sector

The Union Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman announced the opening of eight sectors in May 2020 as part of the INR 20 lakh crore (USD 300 billion) Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliant India Campaign). Space was one of the sectors that opened up as part of these reforms.

The Government said that it wanted the private sector to be a player in the space sector. She said that the Government would provide a level playing field for the non-governmental private entities to build satellites, launch vehicles, and provide space-based services. She promised that future planetary exploration and human outer space travel opportunities would be open to non-governmental private entities. Towards this, she promised access to facilities of India’s space agency, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), and a liberal geospatial policy.

India identified that space held a huge commercial potential for growth. It wanted non-governmental private entities (NGPEs) to be part of this growth. When the Government says NGPEs it is referring to academic institutions, start-ups, and industry.

As a part of opening up the space sector, NewSpace India Ltd (NSIL), which was set up in the previous year, was repurposed to drive a move from a supply-driven to a demand-driven model. NSIL would act as an aggregator of demands from the market. It would then supply the services provided earlier by ISRO. For this, it would take over ownership of ISRO’s operational launch vehicle and satellite fleet. It would commercialize the production of the launch vehicle fleet by handing it over to a private consortium.

The opening up also involved setting up a regulator, Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe). IN-SPACe would provide a one-stop shop for all space-related activities in India. ISRO would then concern itself with the research and development of various space technologies and applications.

IN-SPACe would “promote, hand hold, permit, monitor and supervise space activities by NGPEs and accord necessary permissions as per the regulatory provisions, exemptions and statutory guidelines”.

Developments since the Announcement

A draft Space Activities Bill, 2017 had been floated for comments from stakeholders and the public. This bill was to provide an overall legal framework for the space sector. As of February 2022, the bill has completed public and legal consultations and has been sent to the various Ministries for their approval.

IN-SPACe was established. Pawan Goenka, a former Managing Director of the Indian automobile major, Mahindra & Mahindra, was made Chairman of IN-SPACe. It was reported in February 2022 that ISRO facilities and expertise were extended to the NGPEs. ISRO facilities are being shared with these private entities at no or reasonable cost basis.

NSIL undertook its first fully commercial launch for Brazil’s Amazonia 1 and fourteen ride-share satellites in February 2021, on the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle’s (PSLV) PSLV-C51 mission. It is also undertaking the first demand-driven communication satellite [PDF] launch. It will launch the GSAT-24 communications satellite to fulfill the demand of Direct-to-Home company, Tata Sky (now Tata Play). The launch is expected to take place on board the European Ariane V in the first half of this year.

The Department of Space had provided various draft policies on its website for comments. These include draft policies on Space Communications, Remote Sensing, Technology Transfer, Navigation, Space Transportation, Space exploration and Space Situational Awareness, and Human Spaceflight through 2020 and 2021. India, at present, has, only Space Communications and Remote Sensing policies.

Although space startups have been present in India since 2011, there was a real acceleration in the number of startups that started following the opening up of the space sector. As per statistics shared by the Indian Government in February 2022, there are more than 50 space startups presently in India. These work in areas such as building satellites, launch vehicles, satellite subsystems like electric propulsion systems, as well as various space-based applications in remote sensing, agriculture, fisheries, economic growth forecasting, etc. The Indian Government hopes to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in the space sector.

Obstacles in the Way

As with any reform, there is a feeling that the reforms are not being implemented fast enough. It is not known when the draft Space Activities bill would be cleared by the Union Government and tabled in Parliament. The Space Communications policy is expected to be finalized by April 2022. The status of the other policy drafts is currently not known.

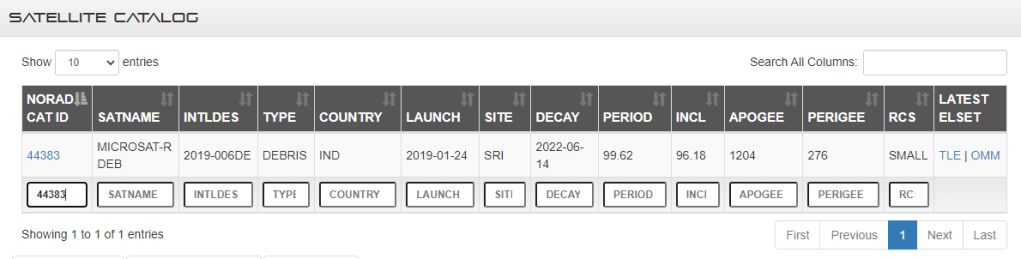

In the interim, ISRO is tasked with clearing the backlog of remote sensing, communication, navigation, scientific, and interplanetary missions of national importance which have been delayed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. India has only had 5 launches from India since 2020. One of them was a failure. There are limits on the number of launches ISRO is able to do in a financial year (March to April). This period of transition would be a difficult one to manage at ISRO, as it would have to fulfill launches for NSIL as well.

NSIL floated tenders for the commercialization of the PSLV in 2019. It has still not been announced as to who the tender is awarded to. There are two other operational launch vehicles, the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) and the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV Mk-III) that also need to be similarly commercialized.

All these delays then make the regulator, In-SPACe ineffective to do much other than provide access to DoS facilities until there is regulatory clarity with the publication of draft policies and the passage of the draft Space Activities Bill in Parliament.

Hopeful Future?

While it is expected that the infrastructure put in place after the announcement of the space reforms, would take anywhere from half a decade to a decade, the future remains hopeful.

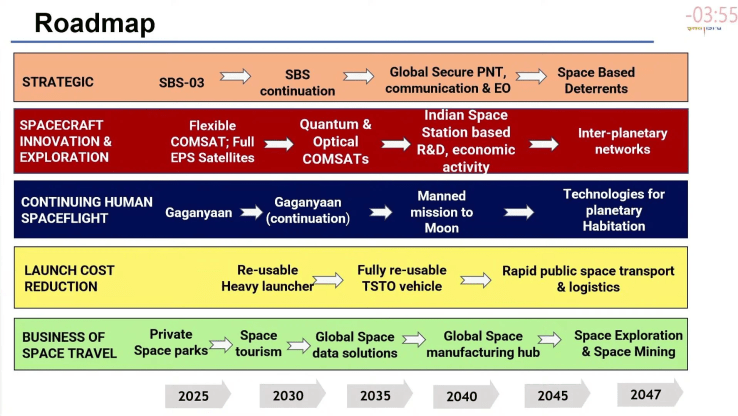

In the decade, India expects to launch interplanetary missions to the Moon, Mars, and Venus. It also expects to operationalize its human spaceflight program in the first half of this decade. In addition, it expects to launch missions for communications, remote sensing, navigation, and scientific applications.

It is expected that these reforms would bear fruit in the future decades. India hopes to participate and play a bigger role in the global space economy. It hopes that its start-ups today will provide goods and services not only for India but also for the world.