ThePrint published an opinion piece by Carnegie India’s Konark Bhandari and Tejas Bharadwaj on 7 November 2022. I am writing this piece to point out certain mistakes in the arguments that they make.

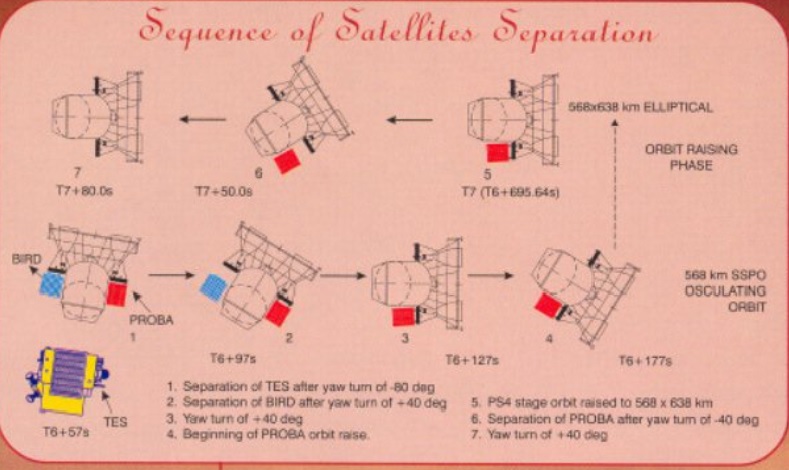

The Indian Space Research Organisation, or ISRO, launched 36 satellites of OneWeb last week. OneWeb, a joint venture between the UK government and India’s Bharti Enterprises, had been scampering to secure a launch of its satellites after its original partner, the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, backed out following the war in Ukraine. There seemed to be no backup available for OneWeb, with analysts citing SpaceX as the only possible option.

Roscosmos was the launch provider. Arianespace was the launch partner. OneWeb backed out on the back of unreasonable demands from Roscosmos. The link they provided in “backed out” in the link clarifies this.

This launch by ISRO, therefore, is seminal. It has defied market expectations. It has done the launch in record time.

The record-time launch defying market expectations was done by postponing the Chandrayaan 3 mission for which the launch vehicle was slated to be used. When SpaceX is able to do a launch a week, making such a claim makes no sense. SpaceX did not launch as fast as India did because it simply prioritized its missions better than India did.

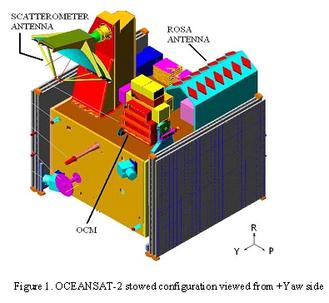

It was also the first mission that did not use India’s traditional workhorse vehicle, the PSLV, but instead opted for the more sophisticated GSLV-Mk III. And it has further catapulted ISRO, and by extension India, as a promising and emerging player in the commercial launch market. To be sure, India did undertake commercial launches for other customers earlier as well, but the speed with which ISRO launched OneWeb’s satellites, and their overall significance, was truly a noteworthy milestone.

ISRO has traditionally flown commercial missions on the workhorse PSLV mission. This is the first time ISRO flew a commercial mission on the GSLV Mk-III. OneWeb’s 36 satellites weighed more than 5,000 kg. PSLV could not deliver that payload to the intended orbit. GSLVMk-III was the only Indian launch vehicle capable of doing the job.

ISRO was able to deliver the launch at this speed because it postponed the launch of Chandrayaan. This would have been “a noteworthy milestone” if ISRO had built a new GSLV Mk-III at this time and fulfilled the demand.

Given India’s increased capability and an enhanced appetite to undertake launches for overseas customers, is it possible to expand the scope of these activities? Could India not just launch small satellite constellations but also build them? Could it do this not just for private enterprises but also countries as well? India should use its capabilities in space infrastructure to undertake deft space diplomacy, with a focus on small satellites. This may fulfil a variety of objectives.

Because of the point above, there has been no increased capability. They are working on increasing the capacity.

Therefore, India can and should think about entering this domain that enables smaller and less “space-capable” states to build their defensive capabilities for peaceful purposes. While SpaceX currently provides access to its Starlink terminals only to its customers, and has cited “cost” as a factor in possibly pulling such access from Ukraine, India should consider providing an entire vertical stack to other countries, including capacity building related to imparting technical “know-how”. This could be done by building, launching and providing access to small satellites to nations that wish to utilise the benefits arising from such services. Besides using them for defence purposes, these benefits accrue in the domains of precision farming, disaster management, and climate change impact measurement.

There are significant obstacles that stop India from providing countries entire spacecraft stacks or even launch services. Many originate from US’s ITAR norms.

Logistically speaking, even for countries that may possess such satellite building capability, launching them in a timely and cost-effective manner is often a challenge. Many small satellites have to often operate as secondary payload on most rocket launches. The more thrust a rocket has, the more payload it can carry. Accordingly, since there are various payloads on a rocket, small satellites usually have to take a back seat and essentially “rideshare” with other payloads whose readiness determines the overall launch schedule. India, with its newly built SSLV, has demonstrated that it can address this logjam too. In fact, ISRO had developed the SSLV keeping in mind lighter payloads weighing less than 500 kg, which are usually used to provide Internet access in remote areas.

Small satellites fly as rideshare when launch vehicles have additional payload-carrying capacity after carrying a primary satellite. This is one of the ways that smaller satellites can launch faster rather than wait for a dedicated launch vehicle to launch them. Rideshare is one of the solutions to the problem that is described above.

Each satellite in a constellation of satellites that provide internet access in remote areas may weigh less than 500 kg. But, to provide continuous internet access, more than one of these sub-500 kg satellites is needed. SSLV would take a long time to launch satellite constellations. GSLV Mk-III is better suited for this role.

We are also waiting for the first successful flight of the SSLV. So, we are awaiting the demonstration of the launch vehicle that can address the logjam.

As luck would have it, India’s domestic policy matrix as well as the international regulatory scenario are currently aligned with these geopolitical aims. India’s freshly proposed telecommunication bill might just make it easier for satellite spectrum to be cheaper – which could help with the adoption of satellite terminals and then help drive use of satellite broadband. A larger satellite broadband user base may effectively drive down the cost per terminal and help ISRO, which itself entered the market for providing satellite broadband last month, to cross-subsidise other countries’ adoption of such satellites.

ISRO has not entered the market for providing satellite broadband. Two of ISRO satellites – the GSAT-11 and GSAT-29 – will be used by a consortium of Hughes Telecommunications India and Bharti Airtel to provide satellite internet services to enterprises (like Jio and SBI) in India and hopefully, also to remote parts of India like Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, and Himachal Pradesh.

In addition to this, with the new US FCC rules mandating deorbiting going into effect (and with FCC being the de-facto global space regulator), de-orbiting may become a more common phenomenon, thereby providing opportunities for Indian companies that specialise in deorbiting satellites which have completed their missions. Given the increasing frequency of small satellite launches and the need for their replacement/deorbiting every now and then, this is eminently feasible. At the same time, there is a valid fear that this may lead to congestion in outer space over time, but India is currently chairing the Working Group on UNCOPUOS LTS Guidelines that is promoting the implementation of existing guidelines as well as discussing the possibilities of developing new guidelines to address the sustainability issues of small satellites, including satellite constellations.

There may be Indian companies working on deorbiting satellites but there are none with such demonstrated capability. It can increase its order book size but I am not sure how much they can deliver until they demonstrate capability.

It would be interesting to see India’s response in the Working Group as the partly Indian-owned company OneWeb may be one of the affected parties of these rules.

However, challenges remain. India would need to ensure that the benefits provided by its small satellites are unique and not in conflict with any existing space programmes of partner/beneficiary nations. Furthermore, the gap between promise and performance must also be addressed since there is a perception that India’s other bilateral infrastructure projects have been afflicted by delays, whatever the cause may be. In the end, India has an opportunity to share the manifold benefits of its prowess in space with other countries. It must do so actively as a form of space diplomacy. Space has always been characterised as a part of the global commons. India can now validate this axiom to the advantage of the comity of nations.

Space is presently an opportunity for collaboration and data-sharing. As a part of space diplomacy, it must share data from its small but aging fleet of remote-sensing satellites. It must provide the services it already does for disaster management and search and rescue operations.

ISRO must first work on the gap between promise and performance for its own fleet of satellites (remote-sensing, communications, and navigation) and missions like Chandrayaan 3.

My prescriptions

Space was characterized as a part of the global commons, but it is falling apart today. I think India must try to make sure that outer space becomes part of a global commons, parts of which (like the Moon and Mars) are opened up for competition and commercial exploitation after all countries are consulted through mechanisms like UN-COPUOS.

On the question asked in the sub-heading of the article, on whether India must now build small satellites and forge global partnerships? I do not know.